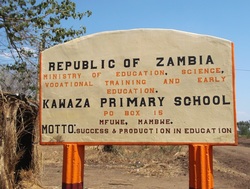

This past weekend I had a chance to visit Kawaza Primary School in Mwufe, a ten-hour multiple bus ride from Lusaka in the Eastern Province. This allowed me to contrast the energy problems experienced by the peri-urban schools that I’ve visited in Lusaka’s compounds with a rural village school. To my surprise, it was the similarities that were striking.

Kawaza averages 30 students per class with two classes per grade. The school serves the surrounding villages that lie within a few kilometres. One block of the school is electrified and is used primarily for Grades 7 to 9 for nighttime study. None of the students have electricity in their homes and access to working radios is scarce; they report to school late in the afternoon to enable them to study with electricity.

Like the majority of the schools I visited in compounds, the school does not have computers or working radios. Schools in both locations had the big and colourful Lifeline radios of the past and used them to access the Learning at Taonga Market distance education programme. Children participating in Taonga Market used to be able to access quality school lessons anywhere initiative the country. Unfortunately, the Taonga Market programme is only being broadcast on community radio stations and not by the national broadcaster, ZNBC, as it once was. The high cost of on-air broadcasting fees was is the main problem.

The schools miss Taonga Market. Christopher Yambayamba, the head of Kawaza Primary, spoke of how the students not only loved the interactive nature of radio learning, but that their grades improved when the school had the programme. He believed the students also learned listening and attention skills quicker through the radio programme. At one time students even came to schools on Saturdays to hear the education programmes and then were tested on what they had learned during the week.

Kawaza Primary School also shares similar issues with access to information as schools in the compounds in Lusaka. Abigail Chimba, the Grade 2 teacher, explained that because they were not a community school, they were told that their solar and wind-up radio did not qualify to be replaced when it finally died. The radio was more than five years old.

The lack of radio not only makes it difficult for schools, but also for community information access, especially during the rainy season. Travel becomes more difficult because the few dirt roads flood quickly, which isolates the villages and schools. They must rely on a few secondhand cellphones to reach relatives in different villages to hear even local news and connect with each other.

Despite the different locations of schools across ZambiaZambia, whether deep rural or urban, the root of the issue involves the lack of reliable energy and poverty. available. It really struck me how Kawaza experienced the same education issues as those schools I've visited in the city and how poverty transcends geography. Despite the distance from Lusaka’s compounds, Kawaza had the same issues regarding education.

Kawaza averages 30 students per class with two classes per grade. The school serves the surrounding villages that lie within a few kilometres. One block of the school is electrified and is used primarily for Grades 7 to 9 for nighttime study. None of the students have electricity in their homes and access to working radios is scarce; they report to school late in the afternoon to enable them to study with electricity.

Like the majority of the schools I visited in compounds, the school does not have computers or working radios. Schools in both locations had the big and colourful Lifeline radios of the past and used them to access the Learning at Taonga Market distance education programme. Children participating in Taonga Market used to be able to access quality school lessons anywhere initiative the country. Unfortunately, the Taonga Market programme is only being broadcast on community radio stations and not by the national broadcaster, ZNBC, as it once was. The high cost of on-air broadcasting fees was is the main problem.

The schools miss Taonga Market. Christopher Yambayamba, the head of Kawaza Primary, spoke of how the students not only loved the interactive nature of radio learning, but that their grades improved when the school had the programme. He believed the students also learned listening and attention skills quicker through the radio programme. At one time students even came to schools on Saturdays to hear the education programmes and then were tested on what they had learned during the week.

Kawaza Primary School also shares similar issues with access to information as schools in the compounds in Lusaka. Abigail Chimba, the Grade 2 teacher, explained that because they were not a community school, they were told that their solar and wind-up radio did not qualify to be replaced when it finally died. The radio was more than five years old.

The lack of radio not only makes it difficult for schools, but also for community information access, especially during the rainy season. Travel becomes more difficult because the few dirt roads flood quickly, which isolates the villages and schools. They must rely on a few secondhand cellphones to reach relatives in different villages to hear even local news and connect with each other.

Despite the different locations of schools across ZambiaZambia, whether deep rural or urban, the root of the issue involves the lack of reliable energy and poverty. available. It really struck me how Kawaza experienced the same education issues as those schools I've visited in the city and how poverty transcends geography. Despite the distance from Lusaka’s compounds, Kawaza had the same issues regarding education.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed